Quick wins for everyday enablement: Lessons from the ADI World Alzheimer Report on rehabilitation

The latest ADI World Alzheimer Report shines a light on rehabilitation in dementia care. Dementia Learning Centre Director Caroline Bartle highlights some important practical insights.

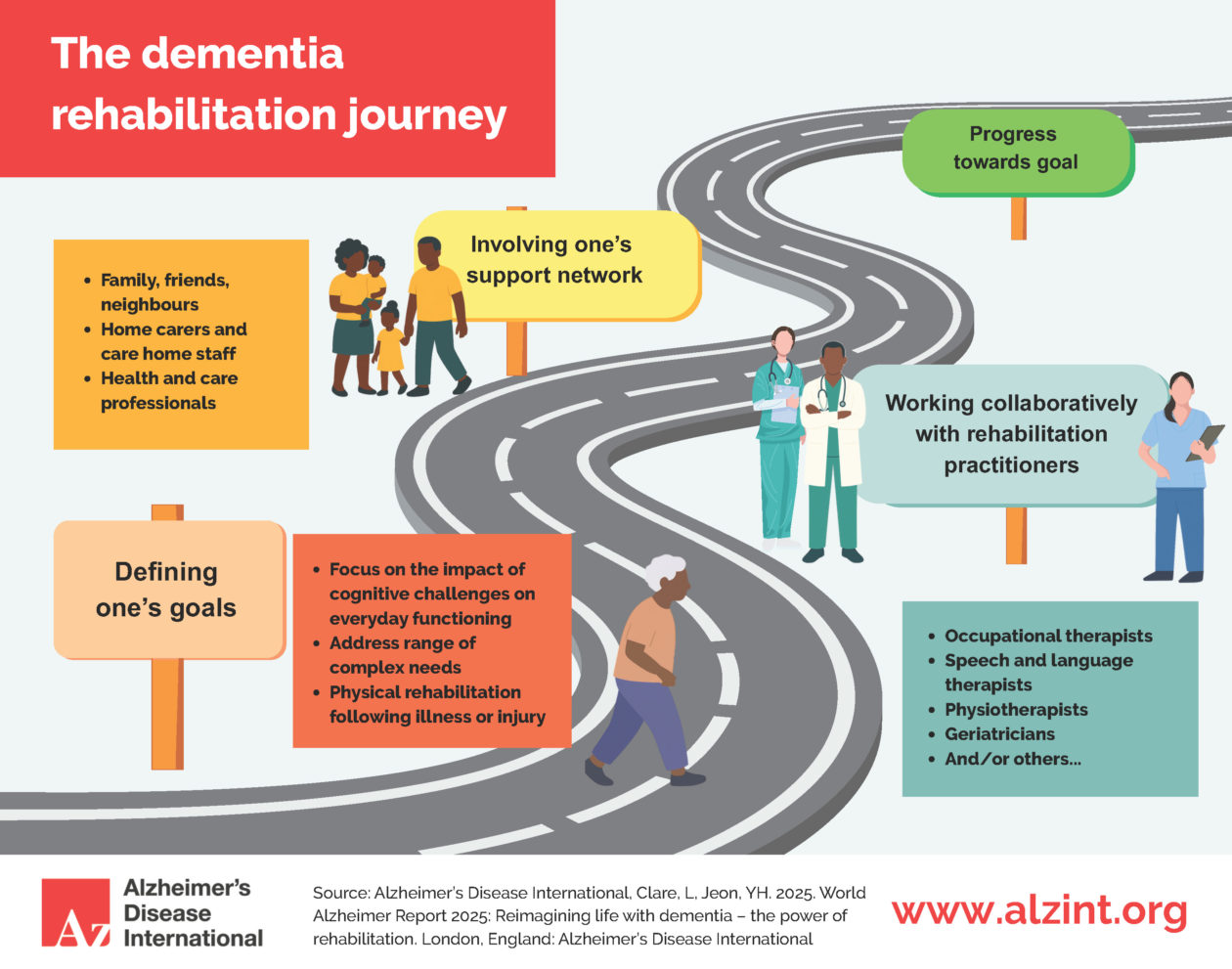

The latest Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI) World Alzheimer Report focuses specifically on rehabilitation in dementia care, bringing together research findings and perspectives from thought leaders.

While rehabilitation might sound like something requiring specialist teams and resources, I’ve distilled key insights from this report and highlighted quick wins that we can apply in everyday practice. Something I call ‘enablement’.

Start with understanding: The foundation of enablement

Loren Mowszowski and Jacqueline Wesson’s research reveals a fundamental truth: enablement begins with truly knowing what a person can and cannot do. Too often, people with dementia mate wareware receive blanket labels like “dependent” or “confused” without careful assessment of their cognitive strengths and functional abilities.

This represents a missed opportunity. Their work demonstrates that effective dementia practice moves beyond diagnostic categories to identify specific challenges in memory, attention, visuospatial skills, or planning, and crucially, how these interact with everyday tasks. In an enablement approach, this knowledge creates the right scaffolding building on what remains possible, compensating where needed, and opening opportunities for meaningful participation.

Small changes, big Impact: Environmental enablement

Environmental modifications often get dismissed as “nice to have” rather than essential enablement tools. Yet Nathalie Bier and Aida Suarez Gonzalez’s chapter on visuospatial and perceptual challenges shows how simple adjustments can dramatically improve independence.

Consider the difference between cluttered surfaces versus clear sightlines, or random item placement versus consistent locations. Adding texture for touch recognition or enhancing visual contrast might seem minor, but these modifications can restore a person’s ability to navigate their world confidently.

Supporting people and their whānau to understand these small changes in their own homes is just as important as adapting residential or community settings. Tools like the EDIE training programme are powerful mechanisms for highlighting these everyday practices, helping staff and families see the world through the eyes of a person living with dementia mate wareware and identify simple, practical adjustments that build confidence and independence.

This connects directly to New Zealand’s emerging dementia design standards an exciting piece of mahi that’s happening right now. This work wisely integrates environmental design with models of care, and it’s really going to elevate this space by providing practical tools where they’re much needed. The message is that physical environment and care practice must work together one without the other misses the enablement potential.

Beyond capability: Why motivation matters

Loren Mowszowski’s work on motivation introduces the COM-B model Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation as a framework for understanding why enablement efforts succeed or fail. Her work reveals that developing capability alone is insufficient. People also need opportunities to practice in supportive contexts and, critically, the motivation to persist.

This has profound implications for practice. Previous ADI reports have noted how self-stigma can undermine motivation, with people withdrawing not from lack of skill but from fear or shame. Addressing motivation therefore means addressing stigma and creating environments where people feel safe to try, fail, and try again.

The power of routine and flexibility

Maureen Schmitter-Edgecombe and Katelyn Brown’s insights on “finding the rhythm” offer a nuanced understanding of how structure and flexibility can coexist. They show that predictable routines provide confidence, while preserved choice maintains dignity and joy preserving personhood through honouring both security and self-determination.

Their approach emphasises practical strategies for building supportive routines: making new habits stick by connecting them to daily routines already in place, using consistent cues and triggers, and starting small with one or two strategies before building complexity. They demonstrate how consistency keeping tools in the same spot, maintaining predictable timing helps compensatory strategies become more automatic and easier to use over time.

Central to this is supported decision-making: we don’t just make decisions for people about maintaining routines because it’s “good for memory”. Their work shows that effective routine-building requires flexibility to adjust expectations on difficult days and the wisdom to know when to step back rather than push through resistance.

Identity and memory as rehabilitation tools

Reinhard Guss’s approach to cognitive rehabilitation offers a compelling model for integrating identity work into everyday practice. His observation that “the person’s greatest fear is forgetting their own history and identity” points to a powerful intervention opportunity.

Supporting someone to compile their timeline, create a life story book, or engage in autobiographical writing serves dual purposes deepening memory while creating practical memory aids. This approach demonstrates how therapeutic and practical benefits can be seamlessly integrated into routine care.

Building workforce capability

The report’s emphasis on workforce education acknowledges a crucial reality: enablement principles must be embedded across the entire care workforce, not just among specialists. Research by Jill Manthorpe and colleagues shows that training in rehabilitation approaches, open questioning, and environmental adaptations can transform ordinary care interactions.

The Dementia Learning Centre has a pivotal role in driving these conversations forward in Aotearoa New Zealand. There’s a clear need for a strong voice around evolving national dementia standards something we currently lack in New Zealand. The expertise and practical insights emerging from rehabilitation research need to be translated into standards that guide practice across all settings.

Implementation realities

What we can take from this report is these simple messages that we can implement day to day:

- Systematic assessment that identifies strengths alongside challenges

- Environmental modifications that reduce barriers and support navigation

- Motivation-focused approaches that address stigma and build confidence

- Routine-based interventions that balance predictability with choice

- Identity-preserving activities that integrate memory work with practical support

- Workforce development that builds capability across all care roles

The path forward

The evidence is compelling, but implementation requires honest acknowledgment of current barriers. Beyond resource constraints, we face entrenched attitudes about what’s possible for people with dementia mate wareware, regulatory frameworks that prioritize safety over autonomy, and care cultures resistant to change.

One striking observation about the report is that strengths-based language isn’t used more consistently throughout the expert chapters. It appears primarily in Emily Ong’s vital and compelling case study where she describes her own experience with cognitive rehabilitation. Her first-person perspective on using “strength-based SMART personalised learning goals” offers invaluable insights from someone actually living with the condition, highlighting how focusing on existing capabilities rather than deficits can be transformative.

Moving forward means starting where we are. Services can begin by auditing their current practices against enablement principles, identifying quick wins that require attitude shifts rather than additional resources, and gradually building capability for more comprehensive approaches.

The goal isn’t perfection it’s progress toward a system where every interaction either maintains or enhances a person’s capacity for independence, dignity, and joy.

If you’re interested in advancing enablement practice in New Zealand, the Dementia Learning Centre welcomes conversations about developing practical implementation frameworks that translate this research into sustainable practice change.

Reference

Alzheimer’s Disease International (2025). World Alzheimer Report 2025: Reimagining life with dementia – the power of rehabilitation. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International.