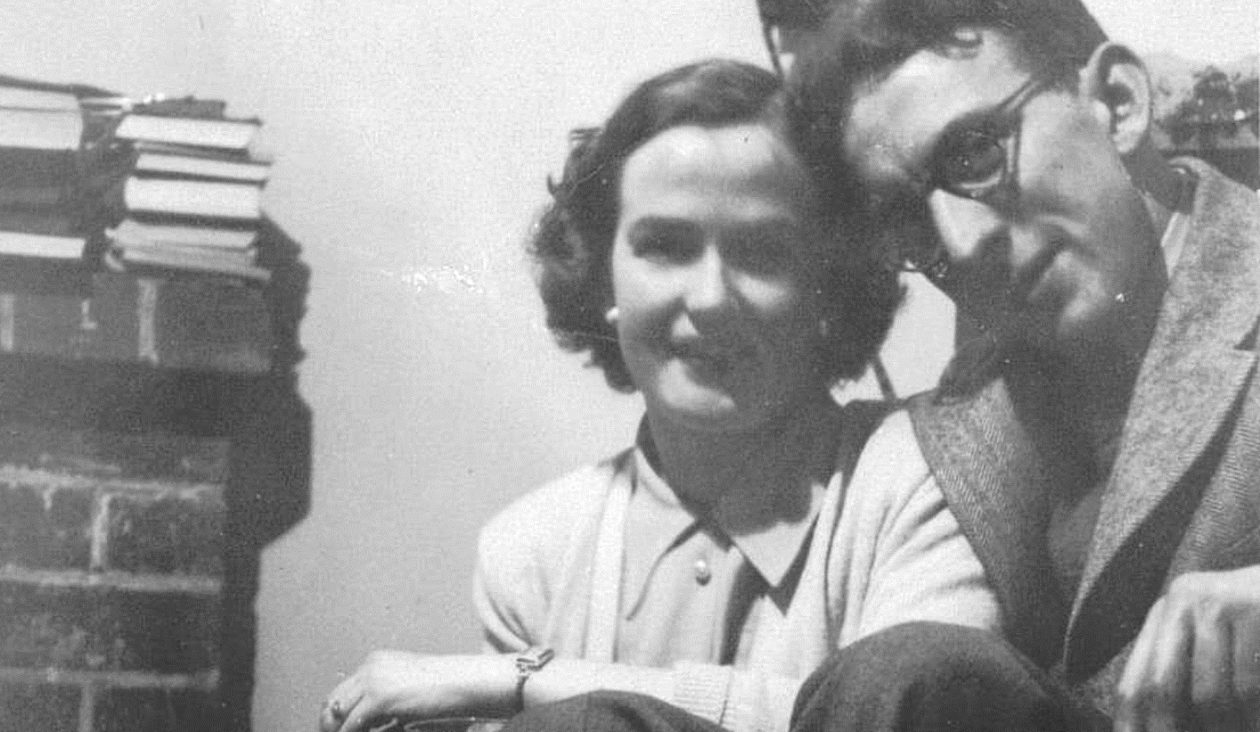

Pip’s story

Since my memoir 'Song for Rosaleen' came out, I’ve received over a hundred messages. Some have been from people who know me and Mum and our family. Many have been from strangers caught up in their own struggles with dementia, as we were.

Since my memoir Song for Rosaleen came out, I’ve received over a hundred messages. Some have been from people who know me and Mum and our family. Many have been from strangers caught up in their own struggles with dementia, as we were.

A young mother sent me a photo of her grandmother and baby son, cheeks pressed, with the message: ‘My grandfather used to bring her weekly to hold and play with my boys – a way to bring some calm to her chaotic day.’ A daughter wrote of looking after her mother who had Alzheimers disease: ‘I still feel terrible guilt that I didn’t make the right decisions or do the most I could.’ A community care worker said my book had reground her and reminded her ‘of the wide, sweeping storm that is the dementia journey’.

I am grateful to all these people, not only for reading Song for Rosaleen but for sharing their feelings with me. Their honest, heartfelt messages have eased my misgivings about thrusting Mum and my five siblings into the public spotlight. What happened to us wasn’t unique. We’re just one of thousands of New Zealand families who’ve found themselves face-to-face with this distressing disease. But telling our story seems to have opened up the space for others to tell theirs.

Why is this so important? Because story-telling is the way we tap into our shared humanity. Stories help us make sense of our world; they connect and console us. As American Buddhist nun Pema Chodron says, ‘There’s something enormously comforting about being able to say, “Other people feel this”.’

This is particularly true of dementia, I think, where confusion, fear and shame tend to isolate not only the person with the disease but everyone around them.

Comparing notes, we discover how much we have in common. ‘For me, it was realising that I was not the only one of the many children of older parents who was being growled at for taking away car keys and other happenings as mentioned in your book,’ said one woman.

A daughter from a big family said, ‘The similarities between you guys and our situation was incredible. I think all nine of us have read it now and we often say, “Remember how in Rosaleen’s case ….”’

Another said, ‘It has made me feel more accepting and more loving of my own Mum as she is now.’

This reminds me that when we stand back and reflect on the rollercoaster that is dementia, we find compassion – not only for our loved ones but for ourselves. ‘Your description of the emotional journey is a beacon along the way for us all to learn from,’ wrote a GP (one of the few men to contact me) whose parents both have the disease.

I don’t know how our society is going to deal humanely with the looming dementia epidemic. But I do believe the answers will come out of brave, frank exchanges like the messages I’ve received. People with dementia and their families may not be health experts but we’re experts on the front line. Our voices are crucial to the solutions.

Pip Desmond

You can get in touch with Pip by email to order a copy of Song for Rosaleen for $15 (including postage).